At Ludosphere, we believe that the toys intended to expand a child’s mind shouldn’t shrink their future.

When you hold one of our 3D-printed puzzles, high-contrast cards, or alphabet sets, you might notice they feel robust and durable, just like traditional plastic. But “plastic” is a broad term. To a chemist, it just means a material made of long chains of things made of carbon. To the rest of us, it usually implies “pollution.”

But not all polymers are created equal.

We strictly use PLA (Polylactic Acid), a bioplastic derived from plants, a compostable bioplastic.

But what does that actually mean for the planet?

To understand why we choose these materials over standard options like Polypropylene (PP) from which most toys are made today because it is much cheaper, we have to look at the lifecycle of a toy in three distinct stages: The Origin, The Chemistry, and The Return to Earth.

1. The Origin Story: Fossil Fuels vs. Nature’s Harvest

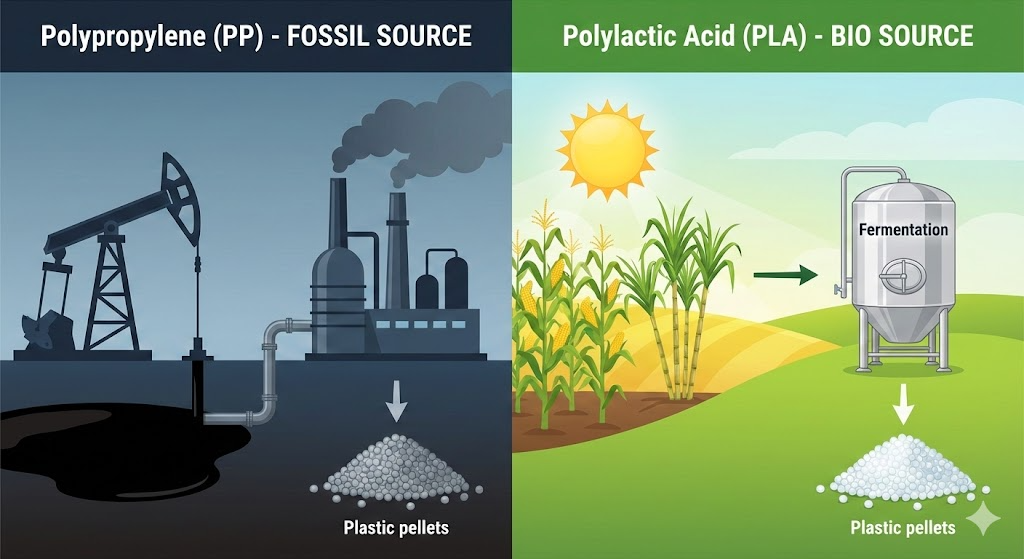

The first major difference happens before the plastic is even made. It starts with sourcing.

Traditional plastics rely on fossil fuel extraction. They require drilling into the earth to pump out crude oil. This oil is refined to eventually become the plastic pellets used in most toys.

Our PLA toys have a much sunnier beginning.

Instead of oil rigs, our story starts on a farm. PLA is made from fermented plant starch (usually corn, sugarcane, or cassava). The plants absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere as they grow. That starch is then harvested and processed in a fermentation tank, similar to how beer or yogurt is made, to create the polymer chains.

2. The Molecular Barrier: Why Water Matters

You might wonder: If they look and feel similar, why is one eco-friendly and the other not?

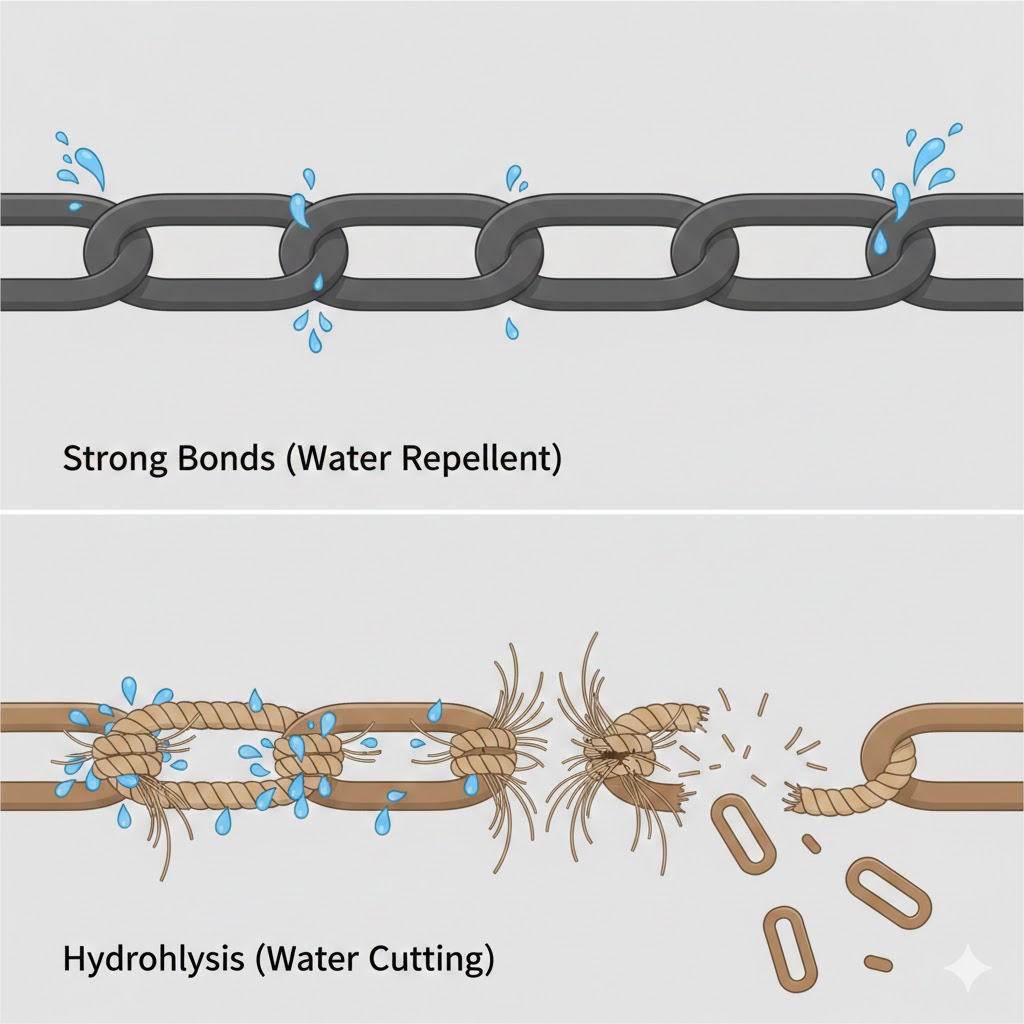

The answer lies under the microscope. It’s all about how the atoms, that form the plastic chain, are bonded together. Traditional plastic (like Polypropylene) creates a molecular “fortress.” It is a solid wall of carbon atoms that is incredibly difficult to break. Water bounces right off it, which is why a plastic bottle can sit in the ocean for centuries without changing.

PLA is different. It is built with a secret “self-destruct” mechanism called an “ester linkage“.

In our bioplastic, the chain of carbon atoms is interrupted by oxygen atoms. Under the right conditions (specifically high heat and moisture found in industrial composting), water molecules act like microscopic scissors. They attack these oxygen “weak points” (hydrolysis) and snip the long polymer chains into tiny, manageable pieces.

It is strong enough to survive dozens of years of rough play in a toddler’s hands, but chemically designed to break down when exposed to the elements of a compost environment.

3. The Digestion Cycle: Microbes at Work

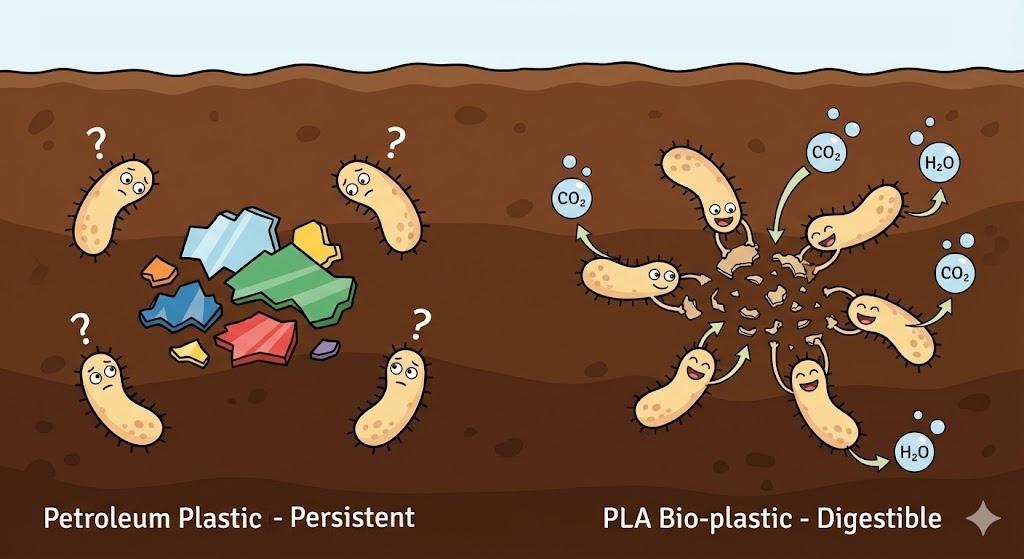

This brings us to the most crucial difference: the End of Life.

When traditional plastic breaks physically (from sun or waves), it doesn’t go away. It just becomes “microplastic”, tiny fragments that persist in the soil and water for hundreds of years. Bacteria in the soil are confused by it; they cannot digest it, so it accumulates.

With PLA, the story has a happy ending.

Once those “molecular scissors” (water) have snipped the PLA into small pieces, microorganisms in the soil can get to work. Because the material came from plants, microbes recognize it as food. They consume the fragments and convert them back into natural elements: carbon dioxide, water, and biomass (humus).

It is a full circle: From the earth, back to the earth.